C#

.NET Core is a development platform that includes a Common Language Runtime (CoreCLR), which manages the execution of code, and a Base Class Library (BCL), which provides a rich library of classes to build applications from.

The C# compiler (named Roslyn) used by the dotnet CLI tool converts C# source code into intermediate language (IL) code and stores the IL in an assembly (a DLL or EXE file).

IL code statements are like assembly language instructions, which are executed by .NET Core's virtual machine, known as CoreCLR.

At runtime, CoreCLR loads the IL code from the assembly, the just-in-time (JIT) compiler compiles it into native CPU instructions, and then it is executed by the CPU on your machine.

The benefit of this three-step compilation process is that Microsoft's able to create CLRs for Linux and macOS, as well as for Windows.

The same IL code runs everywhere because of the second compilation process, which generates code for the native operating system and CPU instruction set.

Regardless of which language the source code is written in, for example, C#, Visual Basic or F#, all .NET applications use IL code for their instructions stored in an assembly.

Another .NET initiative is called .NET Native. This compiles C# code to native CPU instructions ahead of time (AoT), rather than using the CLR to compile IL code JIT

to native code later.

.NET Native improves execution speed and reduces the memory footprint for applications because the native code is generated at build time and then deployed instead of the IL code.

Basics

Comments

| C# | |

|---|---|

Docstring Structure

/** <tag> content </tag> **/

Naming Convention

| Element | Case |

|---|---|

| Namespace | PascalCase |

| Class, Interface | PascalCase |

| Method | PascalCase |

| Field, Property | PascalCase |

| Event, Enum, Enum Value, | PascalCase |

| Variables, Parameters | camelCase |

Namespaces, Imports & Aliases

Hierarchic organization of programs an libraries.

To enable .NET 6/C# 10 implicit namespace imports:

| XML | |

|---|---|

Top Level Statements/Programs (C# 9)

Main Method

Constant Declaration

| C# | |

|---|---|

Assignment Operation

type variable1 = value1, variable2 = value2, ...;

If a variable has not been assigned it assumes the default value.

Input

Screen Output

| C# | |

|---|---|

String Formatting

{index[,alignment][:<formatString><num_decimal_digits>]}

Number Format String

Numeric Format Strings Docs CultureInfo Docs

{index[,alignment][:<formatString><num_decimal_digits>]}

$"{number:C}" formats the number as a currency. Currency symbol & symbol position are determined by CultureInfo.

$"{number:D}" formats the number with decimal digits.

$"{number:F}" formats the number with a fixed number of decimal digits.

$"{number:E}" formats the number in scientific notation.

$"{number:E}" formats the number in the more compact of either fixed-point or scientific notation.

$"{number:N}" formats the number as a measure. Digits separators are determined by CultureInfo.

$"{number:P}" formats the number as a percentage.

$"{number:X}" formats the number as a hexadecimal.

Variable Types

Value Type

A value type variable will store its values directly in an area of storage called the STACK.

The stack is memory allocated to the code that is currently running on the CPU.

When the stack frame has finished executing, the values in the stack are removed.

Reference Type

A reference type variable will store its values in a separate memory region called the HEAP.

The heap is a memory area that is shared across many applications running on the operating system at the same time.

The .NET Runtime communicates with the operating system to determine what memory addresses are available, and requests an address where it can store the value.

The .NET Runtime stores the value, then returns the memory address to the variable.

When your code uses the variable, the .NET Runtime seamlessly looks up the address stored in the variable and retrieves the value that's stored there.

Integer Numeric Types

| Keyword | System Type | Example | Bit/Byte | Min Value | Max Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

sbyte |

System.SByte |

8 bit | -128 | 127 | |

byte |

System.Byte |

8 bit | 0 | 255 | |

short |

System.Int16 |

16 bit | -32'786 | 32'767 | |

ushort |

System.UInt16 |

16 bit | 0 | 65'535 | |

int |

System.Int32 |

123 | 32 bit | -2'47'483'648 | 2'147'483'647 |

uint |

System.UInt32 |

123u | 32 bit | 0 | 4'294'967'296 |

nint |

System.IntPtr |

Arch | 0 | 18'446'744'073'709'551'615 | |

nuint |

System.UIntPtr |

Arch | -9'223'372'036'854'775'808 | 9'223'372'036'854'775'807 | |

long |

System.Int64 |

123l | 64 bit | -9'223'372'036'854'775'808 | 9'223'372'036'854'775'807 |

ulong |

System.UInt64 |

123ul | 64 bit | 0 | 18'446'744'073'709'551'615 |

Floating-Point Numeric Types

| Keyword | System Types | Example | Bit/Byte | Digits | Min Value | Max Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

float |

System.Single |

3.14f | 4 byte | 6-9 | -3.402823 E+38 | 3.402823 E+38 |

double |

System.Double |

3.14 | 8 byte | 15-17 | -1.79769313486232 E+308 | 1.79769313486232 E+308 |

decimal |

System.Decimal |

3.14m | 16 byte | 28-29 | -79'228'162'514'264'337'593'543'950'335 | 79'228'162'514'264'337'593'543'950'335 |

The static fields and methods of the MathF class correspond to those of the Math class, except that their parameters are of type Single rather than Double, and they return Single rather than Double values.

BigInteger

BigInteger represents an integer that will grow as large as is necessary to accommodate values.

Unlike the builtin numeric types, it has no theoretical limit on its range.

Binary & Hexadecimal Numbers

Binary literal: 0b<digits>

Hexadecimal literal: 0x<digits>

| C# | |

|---|---|

Boolean Type (System.Boolean)

bool: true or false

Text Type (System.Char & System.String)

char: single unicode character

string: multiple Unicode characters

Implicit Type

The compiler determines the required type based on the assigned value.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Dynamic Type

| C# | |

|---|---|

Anonymous types (Reference Type)

| C# | |

|---|---|

Index & Range Types (Structs)

A System.Index represents a type that can be used to index a collection either from the start or the end.

A System.Range represents a range that has start and end indexes.

Tuples (Value Type)

Tuples are designed as a convenient way to package together a few values in cases where defining a whole new type wouldn't really be justified.

Tuples support comparison, so it's possible to use the == and != relational operators.

To be considered equal, two tuples must have the same shape and each value in the first tuple must be equal to its counterpart in the second tuple.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Since the names of the attributes of a tuple do not matter (a tuple is an instance of ValueTuple<Type, Type, ...>) it's possible to assign any tuple to another tuple with the same structure.

Tuple Deconstruction

| C# | |

|---|---|

Records

I'ts possible to create record types with immutable properties by using standard property syntax or positional parameters:

it's also possible to create record types with mutable properties and fields:

| C# | |

|---|---|

While records can be mutable, they're primarily intended for supporting immutable data models. The record type offers the following features:

- Concise syntax for creating a reference type with immutable properties

- Built-in behavior useful for a data-centric reference type:

- Value equality

- Concise syntax for nondestructive mutation

- Built-in formatting for display

- Support for inheritance hierarchies

Note: A positional record and a positional readonly record struct declare init-only properties. A positional record struct declares read-write properties.

with-expressions

When working with immutable data, a common pattern is to create new values from existing ones to represent a new state.

To help with this style of programming, records allow for a new kind of expression; the with-expression.

| C# | |

|---|---|

With-expressions use object initializer syntax to state what's different in the new object from the old object. it's possible to specify multiple properties.

A record implicitly defines a protected "copy constructor", a constructor that takes an existing record object and copies it field by field to the new one.

The with expression causes the copy constructor to get called, and then applies the object initializer on top to change the properties accordingly.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Note: it's possible to define a custom copy constructor tha will be picked up by the

withexpression.

with-expressions & Inheritance

Records have a hidden virtual method that is entrusted with "cloning" the whole object.

Every derived record type overrides this method to call the copy constructor of that type, and the copy constructor of a derived record chains to the copy constructor of the base record.

A with-expression simply calls the hidden "clone" method and applies the object initializer to the result.

Value-based Equality & Inheritance

Records have a virtual protected property called EqualityContract.

Every derived record overrides it, and in order to compare equal, the two objects musts have the same EqualityContract.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Strings

.NET strings are immutable. The downside of immutability is that string processing can be inefficient.

If a work performs a series of modifications to a string it will end up allocating a lot of memory, because it will return a separate string for each modification.

This creates a lot of extra work for .NET's garbage collector, causing the program to use more CPU time than necessary.

In these situations, it's possible to can use a type called StringBuilder. This is conceptually similar to a string but it is modifiable.

String Methods (Not In-Place)

Raw string literals

Raw string literals can contain arbitrary text, including whitespace, new lines, embedded quotes, and other special characters without requiring escape sequences.

A raw string literal starts with at least three double-quote (""") characters. It ends with the same number of double-quote characters.

Typically, a raw string literal uses three double quotes on a single line to start the string, and three double quotes on a separate line to end the string.

The newlines following the opening quote and preceding the closing quote aren't included in the final content:

| C# | |

|---|---|

Note: Any whitespace to the left of the closing double quotes will be removed from the string literal.

Raw string literals can be combined with string interpolation to include braces in the output text. Multiple $ characters denote how many consecutive braces start and end the interpolation

Nullable Types

Nullable value types

A nullable value type T? represents all values of its underlying value type T and an additional null value.

Any nullable value type is an instance of the generic System.Nullable<T> structure.

Refer to a nullable value type with an underlying type T in any of the following interchangeable forms: Nullable<T> or T?.

Note: Nullable Value Types default to null.

When a nullable type is boxed, the common language runtime automatically boxes the underlying value of the Nullable<T> object, not the Nullable<T> object itself. That is, if the HasValue property is true, the contents of the Value property is boxed. When the underlying value of a nullable type is unboxed, the common language runtime creates a new Nullable<T> structure initialized to the underlying value.

If the HasValue property of a nullable type is false, the result of a boxing operation is null. Consequently, if a boxed nullable type is passed to a method that expects an object argument, that method must be prepared to handle the case where the argument is null. When null is unboxed into a nullable type, the common language runtime creates a new Nullable<T> structure and initializes its HasValue property to false.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Nullable reference types

C# 8.0 introduces nullable reference types and non-nullable reference types that enable to make important statements about the properties for reference type variables:

-

A reference isn't supposed to be null. When variables aren't supposed to be null, the compiler enforces rules that ensure it's safe to dereference these variables without first checking that it isn't null:

-

The variable must be initialized to a non-null value.

-

The variable can never be assigned the value null.

-

A reference may be null. When variables may be null, the compiler enforces different rules to ensure that you've correctly checked for a null reference:

- The variable may only be dereferenced when the compiler can guarantee that the value isn't null.

- These variables may be initialized with the default null value and may be assigned the value null in other code.

The ? character appended to a reference type declares a nullable reference type.

The null-forgiving operator ! may be appended to an expression to declare that the expression isn't null.

Any variable where the ? isn't appended to the type name is a non-nullable reference type.

Nullability of types

Any reference type can have one of four nullabilities, which describes when warnings are generated:

- Nonnullable: Null can't be assigned to variables of this type. Variables of this type don't need to be null-checked before dereferencing.

- Nullable: Null can be assigned to variables of this type. Dereferencing variables of this type without first checking for null causes a warning.

- Oblivious: Oblivious is the pre-C# 8.0 state. Variables of this type can be dereferenced or assigned without warnings.

- Unknown: Unknown is generally for type parameters where constraints don't tell the compiler that the type must be nullable or nonnullable.

The nullability of a type in a variable declaration is controlled by the nullable context in which the variable is declared.

Nullable Context

Nullable contexts enable fine-grained control for how the compiler interprets reference type variables.

Valid settings are:

- enable: The nullable annotation context is enabled. The nullable warning context is enabled. Variables of a reference type are non-nullable, all nullability warnings are enabled.

- warnings: The nullable annotation context is disabled. The nullable warning context is enabled. Variables of a reference type are oblivious; all nullability warnings are enabled.

- annotations: The nullable annotation context is enabled. The nullable warning context is disabled. Variables of a reference type are non-nullable; all nullability warnings are disabled.

- disable: The nullable annotation context is disabled. The nullable warning context is disabled. Variables of a reference type are oblivious, just like earlier versions of C#; all nullability warnings are disabled.

In Project.csproj:

| XML | |

|---|---|

In Program.cs:

Null Conditional, Null Coalescing, Null Forgiving Operator, Null Checks

Nullable Attributes

It's possible to apply a number of attributes that provide information to the compiler about the semantics of APIs. That information helps the compiler perform static analysis and determine when a variable is not null.

AllowNull: A non-nullable input argument may be null.DisallowNull: A nullable input argument should never be null.MaybeNull: A non-nullable return value may be null.NotNull: A nullable return value will never be null.MaybeNullWhen: A non-nullable input argument may be null when the method returns the specified bool value.NotNullWhen: A nullable input argument will not be null when the method returns the specified bool value.NotNullIfNotNull: A return value isn't null if the argument for the specified parameter isn't null.DoesNotReturn: A method never returns. In other words, it always throws an exception.DoesNotReturnIf: This method never returns if the associated bool parameter has the specified value.

Type Conversion

Converting from any type to a string

The ToString method converts the current value of any variable into a textual representation. Some types can't be sensibly represented as text, so they return their namespace and type name.

Number Downcasting

The rule for rounding (in explicit casting) in C# is subtly different from the primary school rule:

- It always rounds down if the decimal part is less than the midpoint

.5. - It always rounds up if the decimal part is more than the midpoint

.5. - It will round up if the decimal part is the midpoint

.5and the non-decimal part is odd, but it will round down if the non-decimal part is even.

This rule is known as Banker's Rounding, and it is preferred because it reduces bias by alternating when it rounds up or down.

Converting from a binary object to a string

The safest thing to do is to convert the binary object into a string of safe characters. Programmers call this Base64 encoding.

The Convert type has a pair of methods, ToBase64String and FromBase64String, that perform this conversion.

Parsing from strings to numbers or dates and times

The second most common conversion is from strings to numbers or date and time values.

The opposite of ToString is Parse. Only a few types have a Parse method, including all the number types and DateTime.

Preprocessor Directives

C# offers a #define directive that lets you define a compilation symbol.

These symbols are commonly used in conjunction with the #if directive to compile code in different ways for different situations.

It's common to define compilation symbols through the compiler build settings: open up the .csproj file and define the values you want in a <DefineConstants> element of any <PropertyGroup>.

Compilation symbols are typically used in conjunction with the #if, #else, #elif, and #endif directives (#if false also exists).

The .NET SDK defines certain symbols by default. It supports two configurations: Debug and Release.

It defines a DEBUG compilation symbol in the Debug configuration, whereas Release will define RELEASE instead.

It defines a symbol called TRACE in both configurations.

C# provides a more subtle mechanism to support this sort of thing, called a conditional method.

The compiler recognizes an attribute defined by the .NET class libraries, called ConditionalAttribute, for which it provides special compile time behavior.

Method annotated with this attribute will not be present in a non-Debug release.

#error and #warning

C# allows choose to generate compiler errors or warnings with the #error and #warning directives. These are typically used inside conditional regions.

#pragma

The #pragma directive provides two features: it can be used to disable selected compiler warnings, and it can also be used to override the checksum values the compiler puts into the .pdb file it generates containing debug information.

Both of these are designed primarily for code generation scenarios, although they can occasionally be useful to disable warnings in ordinary code.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Expressions & Operators

Primary Expressions

| Syntax | Operation |

|---|---|

x.m |

access to member m of object x ("." → member access operator) |

x(...) |

method invocation ("()" → method invocation operator) |

x[...] |

array access |

new T(...) |

object instantiation |

new T(...){...} |

object instantiation with initial values |

new T[...] |

array creation |

typeof(T) |

System.Type of object x |

nameof(x) |

name of variable x |

sizeof(x) |

size of variable x |

default(T) |

default value of T |

x! |

declare x as not null |

Unary Operators

| Operator | Operation |

|---|---|

+x |

identity |

-x |

negation |

!x |

logic negation |

~x |

binary negation |

++x |

pre-increment |

--x |

pre-decrement |

x++ |

post-increment |

x-- |

post decrement |

(type)x |

explicit casting |

Mathematical Operators

| Operator | Operation |

|---|---|

x + y |

addition, string concatenation |

x - y |

subtraction |

x * y |

multiplication |

x / y |

integer division, |

x % y |

modulo, remainder |

x << y |

left bit shift |

x >> y |

right bit shift |

Relational Operators

| Operator | Operation |

|---|---|

x < y |

less than |

x <= y |

less or equal to |

x > y |

greater than |

x >= y |

greater or equal to |

x is T |

true if x is an object of type T |

x == y |

equality |

x != y |

inequality |

Logical Operators

| Operator | Operation | Name |

|---|---|---|

~x |

bitwise NOT | |

x & y |

bitwise AND | |

x ^ y |

bitwise XOR | |

x | y |

bitwise OR | |

x && y |

evaluate y only if x is true |

|

x || y |

evaluate y only if x is false |

|

x ?? y |

evaluates to y only if x is null, x otherwise |

Null coalescing |

x?.y |

stop if x == null, evaluate x.y otherwise |

Null conditional |

Assignment

| Operator | Operation |

|---|---|

x += y |

x = x + y |

x -= y |

x = x - y |

x *= y |

x = x * y |

x /= y |

x = x / y |

x %= y |

x = x % y |

x <<= y |

x = x << y |

x >>= y |

x = x >> y |

x &= y |

x = x & y |

x |= y |

x = x |

x ^= y |

x = x ^ y |

x ??= y |

if (x == null) {x = y} |

Conditional Operator

<condition> ? <return_if_condition_true> : <return_if_condition_false>;

Decision Statements

If-Else If-Else

| C# | |

|---|---|

Pattern Matching

A pattern describes one or more criteria that a value can be tested against. It's usable in switch statements, switch expressions and if statements.

Switch

The when keyword can be used to specify a filter condition that causes its associated case label to be true only if the filter condition is also true.

Loop Statements

While Loop

Do-While Loop

Executes at least one time.

For Loop

Foreach Loop

Technically, the foreach statement will work on any type that follows these rules:

- The type must have a method named

GetEnumeratorthat returns an object. - The returned object must have a property named

Currentand a method namedMoveNext. - The

MoveNextmethod must return true if there are more items to enumerate through or false if there are no more items.

There are interfaces named IEnumerable and IEnumerable<T> that formally define these rules but technically the compiler does not require the type to implement these interfaces.

Note: Due to the use of an iterator, the variable declared in a foreach statement cannot be used to modify the value of the current item.

Note: From C# 9 it's possible to implementGetEnumerator()as an extension method making enumerable an class that normally isn't.

Example:

| C# | |

|---|---|

Break, Continue

break; interrupts and exits the loop.

continue; restarts the loop cycle without evaluating the instructions.

Yield Statement

| C# | |

|---|---|

Context Statement & Using Declarations

| C# | |

|---|---|

Checked/Unchecked Statements

In checked code block ore expression the mathematic overflow causes an OverflowException.

In unchecked code block the mathematic overflow is ignored end the result is truncated.

It's possible configure the C# compiler to put everything into a checked context by default, so that only explicitly unchecked expressions and statements will be able to overflow silently.

It is done by editing the .csproj file, adding <CheckForOverflowUnderflow>true</CheckForOverflowUnderflow> inside a <PropertyGroup>.

Note: checking can make individual integer operations several times slower.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Exception Handling

Throwing Exceptions

Custom Exceptions

| C# | |

|---|---|

Enums

An enumeration type (or enum type) is a value type defined by a set of named constants of the underlying integral numeric type (int, long, byte, ...).

Consecutive names increase the value by one.

Methods

The method signature is the number & type of the input parameters defined for the method.

C# makes the fairly common distinction between parameters and arguments: a method defines a list of the inputs it expects (the parameters) and the code inside the method refers to these parameters by name.

The values seen by the code could be different each time the method is invoked, and the term argument refers to the specific value supplied for a parameter in a particular invocation.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Expression Body Definition

| C# | |

|---|---|

Arbitrary Number Of Parameter In Methods

| C# | |

|---|---|

Named Arguments

Optional Arguments

The definition of a method, constructor, indexer, or delegate can specify that its parameters are required or that they are optional.

Any call must provide arguments for all required parameters, but can omit arguments for optional parameters.

Each optional parameter has a default value as part of its definition. If no argument is sent for that parameter, the default value is used.

Optional parameters are defined at the end of the parameter list, after any required parameters.

A default value must be one of the following types of expressions:

- a constant expression;

- an expression of the form new ValType(), where ValType is a value type, such as an enum or a struct;

- an expression of the form default(ValType), where ValType is a value type.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Note: If the caller provides an argument for any one of a succession of optional parameters, it must provide arguments for all preceding optional parameters. Comma-separated gaps in the argument list are not supported.

Passing Values By Reference (ref, out, in)

The out, in, ref keywords cause arguments to be passed by reference. It makes the formal parameter an alias for the argument, which must be a variable.

In other words, any operation on the parameter is made on the argument. This behaviour is the same for classes and structs.

An argument that is passed to a ref or in parameter must be initialized before it is passed. However in arguments cannot be modified by the called method.

Variables passed as out arguments do not have to be initialized before being passed in a method call. However, the called method is required to assign a value before the method returns.

Use cases:

out: return multiple values from a method (move data into method)ref: move data bidirectionally between method and call scopein: pass large value type (e,g, struct) as a reference avoiding copying large amounts of data (must be readonly, copied regardless otherwise)

Note: use

inonly with readonly value types, because mutable value types can undo the performance benefits. (Mutable value types are typically a bad idea in any case.)

While the method can use members of the passed reference type, it can't normally replace it with a different object.

But if a reference type argument is marked with ref, the method has access to the variable, so it could replace it with a reference to a completely different object.

Returning Multiple Values with Tuples

Must be C# 7+.

The retuned tuple MUST match the tuple-type in the instantiation

| C# | |

|---|---|

Returning Multiple Values W/ Structs (Return Struct Variable)

| C# | |

|---|---|

Local Functions

Extension Methods

Extension methods allow their usage applied to the extended type as if their declaration was inside the object's class.

Extension methods are not really members of the class for which they are defined.

It's just an illusion maintained by the C# compiler, one that it keeps up even in situations where method invocation happens implicitly.

Note: Extension Method can be declared only inside static classes. Extension methods are available only if their namespace is imported with the

usingkeyword.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Iterators

An iterator can be used to step through collections such as lists and arrays.

An iterator method or get accessor performs a custom iteration over a collection. An iterator method uses the yield return statement to return each element one at a time.

When a yield return statement is reached, the current location in code is remembered. Execution is restarted from that location the next time the iterator function is called.

It's possible to use a yield break statement or exception to end the iteration.

Note: Since an iterator returns an

IEnumerable<T>is can be used to implement aGetEnumerator().

| C# | |

|---|---|

Structs (Custom Value Types) & Classes (Custom Reference Types)

Structure types have value semantics. That is, a variable of a structure type contains an instance of the type.

Class types have reference semantics. That is, a variable of a class type contains a reference to an instance of the type, not the instance itself.

Typically, you use structure types to design small data-centric types that provide little or no behavior. If you're focused on the behavior of a type, consider defining a class.

Because structure types have value semantics, we recommend you to define immutable structure types.

Creating a new instance of a value type doesn't necessarily mean allocating more memory, whereas with reference types, a new instance means anew heap block.

This is why it's OK for each operation performed with a value type to produce a new instance.

The most important question is : does the identity of an instance matter? In other words, is the distinction between one object and another object important?

An important and related question is: does an instance of the type contain state that changes over time?

Modifiable value types tend to be problematic, because it's all too easy to end up working with some copy of a value, and not the correct instance.

So it's usually a good idea for value types to be immutable. This doesn't mean that variables of these types cannot be modified;

it just means that to modify the variable, its contents must be replaced entirely with a different value.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Note: From C# 10 is possible to have a parameterless constructor and make a new struct using a

withstatement. Note: From C# 11 uninitialized values will be filed with their defaults

The only way to affect a struct variable both inside a method and outside is to use the ref keyword;

Modifiers (Methods & Variables)

A locally scoped variable is only accessible inside of the code block in which it's defined.

If you attempt to access the variable outside of the code block, you'll get a compiler error.

partial indicates that other parts of the class, struct, or interface can be defined in the namespace.

All the parts must use the partial keyword.

All the parts must be available at compile time to form the final type.

All the parts must have the same accessibility.

If any part is declared abstract, then the whole type is considered abstract.

If any part is declared sealed, then the whole type is considered sealed.

If any part declares a base type, then the whole type inherits that class.

Methods

Note: if a primary constructor is used all other constructors must use

this(...)to invoke it

Properties & Fields

A field is a variable of any type that is declared directly in a class or struct. Fields are members of their containing type.

A property is a member that provides a flexible mechanism to read, write, or compute the value of a private field.

Note: The

initaccessor is a variant of thesetaccessor which can only be called during object initialization.

Becauseinitaccessors can only be called during initialization, they are allowed to mutatereadonlyfields of the enclosing class, just like in a constructor. Note: creating at least one constructor hides the one provided by default (w/ zero parameters).

Object and Collection Initializers

Object initializers allow to assign values to any accessible fields or properties of an object at creation time without having to invoke a constructor followed by lines of assignment statements.

The object initializer syntax enables to specify arguments for a constructor or omit the arguments (and parentheses syntax).

Static Class

The static keyword declares that a member is not associated with any particular instance of the class.

Static classes can't instantiate objects and all their methods must be static.

Class Members Init Order

Static Field or Method Usage:

- Static field initializers in order of apparition

- Static Constructor

Class Instantiation (new operator):

- Instance field initializers in order of apparition

- Instance Constructor

Object Creation: Class object = new Class(arguments);

Instance Method Usage: object.method(arguments);

Static Method Usage: Class.method(arguments);

Indexers

An indexer is a property that takes one or more arguments, and is accessed with the same syntax as is used for arrays.

This is useful when writing a class that contains a collection of objects.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Abstract Classes

The abstract modifier indicates that the thing being modified has a missing or incomplete implementation.

The abstract modifier can be used with classes, methods, properties, indexers, and events.

Use the abstract modifier in a class declaration to indicate that a class is intended only to be a base class of other classes, not instantiated on its own.

Members marked as abstract must be implemented by non-abstract classes that derive from the abstract class.

abstract classes have the following features:

- An

abstractclass cannot be instantiated. - An

abstractclass may containabstractmethods and accessors. - It is not possible to modify an

abstractclass with thesealedmodifier because the two modifiers have opposite meanings. Thesealedmodifier prevents a class from being inherited and theabstractmodifier requires a class to be inherited. - A non-abstract class derived from an

abstractclass must include actual implementations of all inheritedabstractmethods and accessors.

Note: Use the

abstractmodifier in a method or property declaration to indicate that the method or property does not contain implementation.

abstract methods have the following features:

- An

abstractmethod is implicitly avirtualmethod. -

abstractmethod declarations are only permitted inabstractclasses. -

Because an

abstractmethod declaration provides no actual implementation, there is no method body; the method declaration simply ends with a semicolon and there are no curly braces following the signature. - The implementation is provided by a method override, which is a member of a non-abstract class.

- It is an error to use the

staticorvirtualmodifiers in anabstractmethod declaration.

abstract properties behave like abstract methods, except for the differences in declaration and invocation syntax.

- It is an error to use the

abstractmodifier on astaticproperty. - An

abstractinherited property can be overridden in a derived class by including a property declaration that uses theoverridemodifier.

Cloning

| C# | |

|---|---|

Deconstruction

Deconstruction is not limited to tuples. By providing a Deconstruct(...) method(s) C# allows to use the same syntax with the users types.

Note: Types with a deconstructor can also use positional pattern matching.

Operator Overloading

A user-defined type can overload a predefined C# operator. That is, a type can provide the custom implementation of an operation in case one or both of the operands are of that type.

Use the operator keyword to declare an operator. An operator declaration must satisfy the following rules:

- It includes both a public and a static modifier.

- A unary operator has one input parameter. A binary operator has two input parameters.

In each case, at least one parameter must have type

TorT?whereTis the type that contains the operator declaration.

Nested Types

A type defined at global scope can be only publicor internal.

private wouldn't make sense since that makes something accessible only from within its containing type, and there is no containing type at global scope.

But a nested type does have a containing type, so if a nested type is private, that type can be used only from inside the type within which it is nested.

Note: Code in a nested type is allowed to use nonpublic members of its containing type. However, an instance of a nested type does not automatically get a reference to an instance of its containing type.

Interfaces

An interface declares methods, properties, and events, but it doesn't have to define their bodies.

An interface is effectively a list of the members that a type will need to provide if it wants to implement the interface.

C# 8.0 adds the ability to define default implementations for some or all methods, and also to define nested types and static fields.

Note: Interfaces are reference types. Despite this, it's possible tp implement interfaces on both classes and structs.

However, be careful when doing so with a struct, because when getting hold of an interface-typed reference to a struct, it will be a reference to a box,

which is effectively an object that holds a copy of a struct in a way that can be referred to via a reference.

Generics

Generics Docs Generic Methods Docs

Multiple Generics

| C# | |

|---|---|

Parameters Constraints

Specify an interface or class that the generic type must implement/inherit.

C# supports only six kinds of constraints on a type argument:

- type constraint

- reference type constraint

- value type constraint

notnullunmanagednew()

Inheritance

Classes support only single inheritance. Interfaces offer a form of multiple inheritance. Value types do not support inheritance at all.

One reason for this is that value types are not normally used by reference, which removes one of the main benefits of inheritance: runtime polymorphism.

Since a derived class inherits everything the base class has—all its fields, methods, and other members,

both public and private—an instance of the derived class can do anything an instance of the base could do.

Note: When deriving from a class, it's not possible to make the derived class more visible than its base. This restriction does not apply to interfaces.

Apublicclass is free to implementinternalorprivateinterfaces. However, it does apply to an interface's bases: apublicinterface cannot derive from aninternalinterface.

Downcasting

Downcasting is the conversion from a base class type to one of it's derived types.

Inheritance & Constructors

All of a base class's constructors are available to a derived type, but they can be invoked only by constructors in the derived class.

All constructors are required to invoke a constructor on their base class, and if it's not specified which to invoke, the compiler invokes the base's zero-argument constructor.

If the base has not a zero-argument constructor the compilation will cause an error. It's possible to invoke a base constructor explicitly to avoid this error.

Initialization order:

- Derived class field initializers

- Base class field initializers

- Base class constructor

- Derived class constructor

| C# | |

|---|---|

Generics Inheritance

If you derive from a generic class, you must supply the type arguments it requires.

You must provide concrete types unless your derived type is generic, in which case it can use its own type parameters as arguments.

It's allowed to use derived type as a type argument to the base class. And it's also possible to specify a constraint on a type argument requiring it to derive from the derived type.

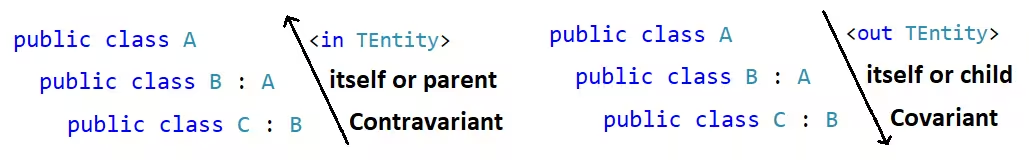

Covariance & Contravariance (only for interfaces)

The theory behind covariance and contravariance in C#

Covariance and Contravariance are terms that refer to the ability to use a more derived type (more specific) or a less derived type (less specific) than originally specified.

Generic type parameters support covariance and contravariance to provide greater flexibility in assigning and using generic types.

- Covariance: Enables to use a more derived type than originally specified.

- Contravariance: Enables to use a more generic (less derived) type than originally specified.

- Invariance: it's possible to use only the type originally specified; so an invariant generic type parameter is neither covariant nor contravariant.

Note: annotate generic type parameters with

outandinannotations to specify whether they should behave covariantly or contravariantly.

Delegates

A delegate is a type that represents a reference to a method with a particular parameter list and return type. Delegates are used to pass methods as arguments to other methods.

This ability to refer to a method as a parameter makes delegates ideal for defining callback methods.

Any method from any accessible class or struct that matches the delegate type can be assigned to the delegate. The method can be either static or an instance method.

This makes it possible to programmatically change method calls, and also plug new code into existing classes.

Multicast Delegates

Multicast Delegates are delegates that can have more than one element in their invocation list.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Note: Delegate removal behaves in a potentially surprising way if the delegate removed refers to multiple methods.

Subtraction of a multicast delegate succeeds only if the delegate from which subtract contains all of the methods in the delegate being subtracted sequentially and in the same order.

Delegate Invocation

Invoking a delegate with a single target method works as though the code had called the target method in the conventional way.

Invoking a multicast delegate is just like calling each of its target methods in turn.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Common Delegate Types

Note: Each delegate has an overload taking from zero to 16 arguments;

| C# | |

|---|---|

Type Compatibility

Delegate types do not derive from one another. Any delegate type defined in C# will derive directly from MulticastDelegate.

However, the type system supports certain implicit reference conversions for generic delegate types through covariance and contravariance. The rules are very similar to those for interfaces.

Anonymous Functions (Lambda Expressions)

Delegates without explicit separated method.

Events

Structs and classes can declare events. This kind of member enables a type to provide notifications when interesting things happen, using a subscription-based model.

The class who raises events is called Publisher, and the class who receives the notification is called Subscriber. There can be multiple subscribers of a single event.

Typically, a publisher raises an event when some action occurred. The subscribers, who are interested in getting a notification when an action occurred, should register with an event and handle it.

Registering Event Handlers

| C# | |

|---|---|

Built-In EventHandler Delegate

.NET includes built-in delegate types EventHandler and EventHandler<TEventArgs> for the most common events.

Typically, any event should include two parameters: the source of the event and event data.

The EventHandler delegate is used for all events that do not include event data, the EventHandler<TEventArgs> delegate is used for events that include data to be sent to handlers.

Custom Event Args

Assemblies

In .NET the proper term for a software component is an assembly, and it is typically a .dll or .exe file.

Occasionally, an assembly will be split into multiple files, but even then it is an indivisible unit of deployment: it has to be wholly available to the runtime, or not at all.

Assemblies are an important aspect of the type system, because each type is identified not just by its name and namespace, but also by its containing assembly.

Assemblies provide a kind of encapsulation that operates at a larger scale than individual types, thanks to the internal accessibility specifier, which works at the assembly level.

The runtime provides an assembly loader, which automatically finds and loads the assemblies a program needs.

To ensure that the loader can find the right components, assemblies have structured names that include version information, and they can optionally contain a globally unique element to prevent ambiguity.

Anatomy of an Assembly

Assemblies use the Win32 Portable Executable (PE) file format, the same format that executables (EXEs) and dynamic link libraries (DLLs) have always used in "modern" (since NT) versions of Windows.

The C# compiler produces an assembly as its output, with an extension of either .dll or .exe.

Tools that understand the PE file format will recognize a .NET assembly as a valid, but rather dull, PE file.

The CLR essentially uses PE files as containers for a .NET-specific data format, so to classic Win32 tools, a C# DLL will not appear to export any APIs.

With .NET Core 3.0 or later, .NET assemblies won't be built with an extension of .exe.

Even project types that produce directly runnable outputs (such as console or WPF applications) produce a .dll as their primary output.

They also generate an executable file too, but it's not a .NET assembly. It's just a bootstrapper that starts the runtime and then loads and executes your application's main assembly.

Note: C# compiles to a binary intermediate language (IL), which is not directly executable.

The normal Windows mechanisms for loading and running the code in an executable or DLL won't work with IL, because that can run only with the help of the CLR.

.NET MEtadata

As well as containing the compiled IL, an assembly contains metadata, which provides a full description of all of the types it defines, whether public or private.

The CLR needs to have complete knowledge of all the types that the code uses to be able to make sense of the IL and turn it into running code, the binary format for IL frequently refers to the containing assembly's metadata and is meaningless without it.

Resources

It's possible to embed binary resources in a DLL alongside the code and metadata. To embed a file select "Embedded Resource" as it's Build Action in the file properties.

This compiles a copy of the file into the assembly.

To extract the resource at runtime use the Assembly class's GetManifestResourceStream method which is par of the Reflection API.

Multifile Assembly

.NET Framework allowed an assembly to span multiple files.

It was possible to split the code and metadata across multiple modules, and it was also possible for some binary streams that are logically embedded in an assembly to be put in separate files.

This feature was rarely used, and .NET Core does not support it. However, it's necessary to know about it because some of its consequences persist.

In particular, parts of the design of the Reflection API make no sense unless this feature is known.

With a multifile assembly, there's always one master file that represents the assembly. This will be a PE file, and it contains a particular element of the metadata called the assembly manifest.

This is not to be confused with the Win32-style manifest that most executables contain.

The assembly manifest is just a description of what's in the assembly, including a list of any external modules or other external files; in a multimodule assembly, the manifest describes which types are defined in which files.

Assembly Resolution

When the runtime needs to load an assembly, it goes through a process called assembly resolution.

.NET Core supports two deployment options for applications:

- self-contained

- framework-dependent

Self-Contained Deployment

When publishing a self-contained application, it includes a complete copy of .NET Core, the whole of the CLR and all the built-in assemblies.

When building this way, assembly resolution is pretty straightforward because everything ends up in one folder.

There are two main advantages to self-contained deployment:

- there is no need to install .NET on target machines

- it's known exactly what version of .NET and which versions of all DLLs are running

With self-contained deployment, unless the application directs the CLR to look elsewhere everything will load from the application folder, including all assemblies built into .NET.

Framework-Dependent Deployment

The default build behavior for applications is to create a framework-dependent executable. In this case, the code relies on a suitable version of .NET Core already being installed on the machine.

Framework-dependent applications necessarily use a more complex resolution mechanism than self-contained ones.

When such an application starts up it will first determine exactly which version of .NET Core to run.

The chosen runtime version selects not just the CLR, but also the assemblies making up the parts of the class library built into .NET.

Assembly Names

Assembly names are structured. They always include a simple name, which is the name by which normally refer to the DLL.

This is usually the same as the filename but without the extension. It doesn't technically have to be but the assembly resolution mechanism assumes that it is.

Assembly names always include a version number. There are also some optional components, including the public key token, a string of hexadecimal digits, which is required to have a unique name.

Strong Names

If an assembly's name includes a public key token, it is said to be a strong name. Microsoft advises that any .NET component that is published for shared use (e.g: made available via NuGet) should have a strong name.

As the terminology suggests, an assembly name's public key token has a connection with cryptography. It is the hexadecimal representation of a 64-bit hash of a public key.

Strongly named assemblies are required to contain a copy of the full public key from which the hash was generated.

The assembly file format also provides space fora digital signature, generated with the corresponding private key.

The uniqueness of a strong name relies on the fact that key generation systems use cryptographically secure random-number generators, and the chances of two people generating two key pairs with the same public key token are vanishingly small.

The assurance that the assembly has ot been tampered with comes from the fact that a strongly named assembly must be signed, and only someone in possession of the private key can generate a valid signature. Any attempt to modify the assembly after signing it will invalidate the signature.

Version

All assembly names include a four-part version number: major.minor.build.revision. However, there's no particular significance to any of these.

The binary format that IL uses for assembly names and references limits the range of these numbers, each part must fit in a 16-bit unsigned integer (a ushort), and the highest allowable value in a version part is actually one less than the maximum value that would fit, making the highest legal version number 65534.65534.65534.65534.

As far as the CLR is concerned, there's really only one interesting thing you can do with a version number, which is to compare it with some other version number, either they match or one is higher than the other.

The build system tells the compiler which version number to use for the assembly name via an assembly-level attribute.

Note: NuGet packages also have version numbers, and these do not need to be connected in any way to assembly versions. NuGet does treat the components of a package version number as having particular significance: it has adopted the widely used semantic versioning rules.

Culture

All assembly names include a culture component.

This is not optional, although the most common value for this is the default neutral, indicating that the assembly contains no culture-specific code or data.

The culture is usually set to something else only on assemblies that contain culture-specific resources. The culture of an assembly's name is designed to support localization of resources such as images and strings.

Reflection

The CLR knows a great deal about the types the programs define and use. It requires all assemblies to provide detailed metadata, describing each member of every type, including private implementation details.

It relies on this information to perform critical functions, such as JIT compilation and garbage collection. However, it does not keep this knowledge to itself.

The reflection API grants access to this detailed type information, so the code can discover everything that the runtime can see.

Reflection is particularly useful in extensible frameworks, because they can use it to adapt their behavior at runtime based on the structure of the code.

The reflection API defines various classes in the System.Reflection namespace. These classes have a structural relationship that mirrors the way that assemblies and the type system work.

Assembly

The Assembly class defines three context-sensitive static methods that each return an Assembly.

The GetEntryAssembly method returns the object representing the EXE file containing the program's Main method.

The GetExecutingAssembly method returns the assembly that contains the method from which it has been called it.

GetCallingAssembly walks up the stack by one level, and returns the assembly containing the code that called the method that called GetCallingAssembly.

To inspect an assembly info use the ReflectionOnlyLoadFrom (or ReflectionOnlyLoad) method of the Assembly class.

This loads the assembly in such a way that it's possible to inspect its type information, but no code in the assembly will execute, nor will any assemblies it depends on be loaded automatically.

Attributes

In .NET, it's possible to annotate components, types, and their members with attributes.

An attribute's purpose is to control or modify the behavior of a framework, a tool, the compiler, or the CLR.

Attributes are passive containers of information that do nothing on their own.

Applying Attributes

To avoid having to introduce an extra set of concepts into the type system, .NET models attributes as instances of .NET types.

To be used as an attribute, a type must derive from the System.Attribute class, but it can otherwise be entirely ordinary.

It's possible to pass arguments to the attribute constructor in the annotation.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Note: The real name of an attribute ends with "Attribute" (

[AttrName]refers to theAttrNameAttributeclass)

Multiple Attributes

Defining Custom Attribute Types

| C# | |

|---|---|

NOTE: From C# 11 attributes can be generic and have type constraints

Retrieving Attributes

It's possible to discover which attributes have been applied through the reflection API.

The various targets of attribute have a reflection type representing them (MethodInfo, PropertyInfo, ...) which all implement the interface ICustomAttributeProvider.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Files & Streams

A .NET stream is simply a sequence of bytes. That makes a stream a useful abstraction for many commonly encountered features such as a file on disk, or the body of an HTTP response.

A console application uses streams to represent its input and output.

The Stream class is defined in the System.IO namespace.

It is an abstract base class, with concrete derived types such as FileStream or GZipStream representing particular kinds of streams.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Some streams are read-only. For example, if input stream for a console app represents the keyboard or the output of some other program, there's no meaningful way for the program to write to that stream.

Some streams are write-only, such as the output stream of a console application.

If Read is called on a write-only stream or Write on a read-only one, these methods throw a NotSupportedException.

Both Read and Write take a byte[] array as their first argument, and these methods copy data into or out of that array, respectively.

The offset and count arguments that follow indicate the array element at which to start, and the number of bytes to read or write.

There are no arguments to specify the offset within the stream at which to read or write. This is managed by the Position property.

This starts at zero, but at each read or write, the position advances by the number of bytes processed.

The Read method returns an int. This tells how many bytes were read from the stream, the method does not guarantee to provide the amount of data requested.

The reason Read is slightly tricky is that some streams are live, representing a source of information that produces data gradually as the program runs.

Note: If asked for more than one byte at a time, a

Streamis always free to return less data than requested from Read for any reason. Never presume that a call toReadreturned as much data as it could.

Position & Seeking

Streams automatically update their current position each time a read or write operation is completed. The Position property can be set to move to the desired location.

This is not guaranteed to work because it's not always possible to support it. Some streams will throw NotSupportedException when trying to set the Position property.

Stream also defines a Seek method, this allows to specify the position required relative to the stream's current position.

Passing SeekOrigin.Current as second argument will set the position by adding the first argument to the current position.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Flushing

Writing data to a Stream does not necessarily cause the data to reach its destination immediately.

When a call to Write returns, all that is known is that it has copied the data somewhere; but that might be a buffer in memory, not the final target.

The Stream class therefore offers a Flush method. This tells the stream that it has to do whatever work is required to ensure that any buffered data is written to its target, even if that means making suboptimal use of the buffer.

A stream automatically flushes its contents when calling Dispose. Flush only when it's needed to keep a stream open after writing out buffered data.

It is particularly important if there will be extended periods during which the stream is open but inactive.

Note: When using a

FileStream, theFlushmethod does not necessarily guarantee that the data being flushed has made it to disk yet. It merely makes the stream pass the data to the OS.

Before callingFlush, the OS hasn't even seen the data, so if the process terminates suddenly, the data would be lost.

AfterFlushhas returned, the OS has everything the code has written, so the process could be terminated without loss of data.

However, the OS may perform additional buffering of its own, so if the power fails before the OS gets around to writing everything to disk, the data will still be lost.

To guarantee that data has been written persistently (rather than merely ensuring that it has been handed it to the OS), use either the WriteThrough flag, or call the Flush overload that takes a bool, passing true to force flushing to disk.

StreamReader & StreamWriter (Text Files)

The most useful concrete text-oriented streams types are StreamReader and StreamWriter, which wrap a Stream object.

It's possible to constructing them by passing a Stream as a constructor argument, or a string containing the path of a file, in which case they will automatically construct a FileStream and then wrap that.

StringReader & StringWriter

The StringReader and StringWriter classes serve a similar purpose to MemoryStream: they are useful when working with an API that requires either a TextReader or TextWriter (abstract text streams), but you want to work entirely in memory.

Whereas MemoryStream presents a Stream API on top of a byte[] array, StringReader wraps a string as a TextReader, while StringWriter presents a TextWriter API on top of a StringBuilder.

Files & Directories

FileStream Class (Binary Files)

The FileStream class derives from Stream and represents a file from the filesystem.

It' common to use the constructors in which the FileStream uses OS APIs to create the file handle. It's possible to provide varying levels of detail on how this si to be done.

At a minimum the file's path and a value from the FileMode enumeration must be provided.

FileMode |

Behavior if file exists | Behavior if file does not exist |

|---|---|---|

CreateNew |

Throws IOException |

Creates new file |

Create |

Replaces existing file | Creates new file |

Open |

Opens existing file | Throws FileNotFoundException |

OpenOrCreate |

Opens existing file | Creates new file |

Truncate |

Replaces existing file | Throws FileNotFoundException |

Append |

Opens existing file, setting Position to end of file | Creates new file |

FileAccess Enumeration:

Read: Read access to the file. Data can be read from the file. Combine with Write for read/write access.Write: Write access to the file. Data can be written to the file. Combine with Read for read/write access.ReadWrite: Read and write access to the file. Data can be written to and read from the file.

FileShare Enumeration:

Delete: Allows subsequent deleting of a file.None: Declines sharing of the current file. Any request to open the file (by this process or another process) will fail until the file is closed.Read: Allows subsequent opening of the file for reading. If this flag is not specified, any request to open the file for reading (by this process or another process) will fail until the file is closed. However, even if this flag is specified, additional permissions might still be needed to access the file.ReadWrite: Allows subsequent opening of the file for reading or writing. If this flag is not specified, any request to open the file for reading or writing (by this process or another process) will fail until the file is closed. However, even if this flag is specified, additional permissions might still be needed to access the file.Write: Allows subsequent opening of the file for writing. If this flag is not specified, any request to open the file for writing (by this process or another process) will fail until the file is closed. However, even if this flag is specified, additional permissions might still be needed to access the file.

FileOptions Enumeration:

WriteThrough: Disables OS write buffering so data goes straight to disk when you flush the stream.AsynchronousSpecifies: the use of asynchronous I/O.RandomAccessHints: to filesystem cache that you will be seeking, not reading or writing data in order.SequentialScanHints: to filesystem cache that you will be reading or writing data in order.DeleteOnCloseTells:FileStreamto delete the file when you callDispose.EncryptedEncrypts: the file so that its contents cannot be read by other users.

Note: The

WriteThroughflag will ensure that when the stream is disposed or flushed, all the data written will have been delivered to the drive, but the drive will not necessarily have written that data persistently (drives can defer writing for performance), so data loss id still possible if the power fails.

| C# | |

|---|---|

File Class

The static File class provides methods for performing various operations on files.

Directory Class

Exposes static methods for creating, moving, and enumerating through directories and subdirectories.

Path Class

FileInfo, DirectoryInfo & FileSystemInfo

Classes to hold multiple info about a file or directory. If some property changes using the method Refresh() will update the data.

CLR Serialization

Types are required to opt into CLR serialization. .NET defines a [Serializable] attribute that must be present before the CLR will serialize the type (class).

Serialization works directly with an object's fields. It uses reflection, which enables it to access all members, whether public or private.

Note: CLR Serialization produces binary streams in a .NET specific format

DateTime & TimeSpan

TimeSpan Struct

Object that represents the difference between two dates

Memory Efficiency

The CLR is able to perform automatic memory management thanks to its garbage collector (GC). This comes at a price: when a CPU spends time on garbage collection, that stops it from getting on with more productive work.

In many cases, this time will be small enough not to cause visible problems. However, when certain kinds of programs experience heavy load, GC costs can come to dominate the overall execution time.

C# 7.2 introduced various features that can enable dramatic reductions in the number of allocations. Fewer allocations means fewer blocks of memory for the GC to recover, so this translates directly to lower GC overhead. There is a price to pay, of course: these GC-efficient techniques add significant complication to the code.

Span<T>

The System.Span<T> (a ref struct) value type represents a sequence of elements of type T stored contiguously in memory. Those elements can live inside an array, a string, a managed block of memory allocated in a stack frame, or unmanaged memory.

A Span<T> encapsulates three things: a pointer or reference to the containing memory (e.g., the string or array), the position of the data within that memory, and its

length.

Access to a span contents is done like an and since a Span<T> knows its own length, its indexer checks that the index is in range, just as the built-in array type does.

Note: Normally, C# won’t allow to use

stackallocoutside of code marked as unsafe, since it allocates memory on the stack producing a pointer. However, the compiler makes an exception to this rule when assigning the pointer produced by astackallocexpression directly into a span.

The fact that Span<T> and ReadOnlySpan<T> are both ref struct types ensures that a span cannot outlive its containing stack frame, guaranteeing that the stack frame on which the stack-allocated memory lives will not vanish while there are still outstanding references to it.

In addition to the array-like indexer and Length properties, Span<T> offers a few useful methods.

The Clear and Fill methods provide convenient ways to initialize all the elements in a span either to the default value or a specific value.

Obviously, these are not available on ReadOnlySpan<T>.

The Span<T> and ReadOnlySpan<T> types are both declared as ref struct. This means that not only are they value types, they are value types that can live only on the

stack. So it's not possible to have fields with span types in a class, or any struct that is not also a ref struct.

This also imposes some potentially more surprising restrictions:

- it's not possible to use a span in a variable in an async method.

- there are restrictions on using spans in anonymous functions and in iterator methods

This restriction is necessary for .NET to be able to offer the combination of array-like performance, type safety, and the flexibility to work with multiple different containers.

Note: it's possible to use spans in local methods, and even declare a ref struct variable in the outer method and use it from the nested one, but with one restriction: it's not possible a delegate that refers to that local method, because this would cause the compiler to move shared variables into an object that lives on the heap.

Memory<T>

The Memory<T> type and its counterpart, ReadOnlyMemory<T>, represent the same basic concept as Span<T> and ReadOnlySpan<T>: these types provide a uniform view

over a contiguous sequence of elements of type T that could reside in an array, unmanaged memory, or, if the element type is char, a string.

But unlike spans, these are not ref struct types, so they can be used anywhere. The downside is that this means they cannot offer the same high performance as spans.

It's possible to convert a Memory<T> to a Span<T>, and likewise a ReadOnlyMemory<T> to a ReadOnlySpan<T>.

This makes these memory types useful when you want something span-like, but in a context where spans are not allowed.

Regular Expressions

Unsafe Code & Pointers

The unsafe keyword denotes an unsafe context, which is required for any operation involving pointers.

In an unsafe context, several constructs are available for operating on pointers:

- The

*operator may be used to perform pointer indirection (Pointer indirection). - The

->operator may be used to access a member of a struct through a pointer (Pointer member access). - The

[]operator may be used to index a pointer (Pointer element access). - The

&operator may be used to obtain the address of a variable (The address-of operator). - The

++and--operators may be used to increment and decrement pointers (Pointer increment and decrement). - The

+and-operators may be used to perform pointer arithmetic (Pointer arithmetic). - The

==,!=,<,>,<=, and>=operators may be used to compare pointers (Pointer comparison). - The

stackallocoperator may be used to allocate memory from the call stack (Stack allocation).

The fixed statement prevents the garbage collector from relocating a movable variable. It's only permitted in an unsafe context.

It's also possible to use the fixed keyword to create fixed size buffers.

The fixed statement sets a pointer to a managed variable and "pins" that variable during the execution of the statement.

Pointers to movable managed variables are useful only in a fixed context. Without a fixed context, garbage collection could relocate the variables unpredictably.

The C# compiler only allows to assign a pointer to a managed variable in a fixed statement.

| C# | |

|---|---|

Native Memory

| C# | |

|---|---|

External Code

The extern modifier is used to declare a method that is implemented externally.

A common use of the extern modifier is with the DllImport attribute when using Interop services to call into unmanaged code.

In this case, the method must also be declared as static.

Magic Methods

Methods needed to implement a behaviour which do not need an interface to work. The methods must be named appropriately and have the correct return type.

Enumerable

Awaitable

| C# | |

|---|---|

Code Quality

Code Analysis

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

None |

All rules are disabled. Can selectively opt in to individual rules to enable them. |

Default |

Default mode, where certain rules are enabled as build warnings, certain rules are enabled as options IDE suggestions, and the remainder are disabled. |

Minimum |

More aggressive mode than Default mode. Certain suggestions that are highly recommended for build enforcement are enabled as build warnings. |

Recommended |

More aggressive mode than Minimum mode, where more rules are enabled as build warnings. |

All |

All rules are enabled as build warnings. Can selectively opt out of individual rules to disable them. |

Dependency Auditing

| XML | |

|---|---|

The auditing of dependencies is done during the dotnet restore step.

A description of the dependencies is checked against a report of known vulnerabilities on the GitHub Advisory Database.

Audit Mode:

- all: audit direct and transitive dependencies for vulnerabilities.

- direct: audit only direct dependencies for vulnerabilities.